For 25 years, I have navigated the world of Individualized Education Programs (IEPs) and 504 Plans, crossing four different states, parenting five children with mental health, and an average age of 12, and applying different parenting skills across two marriages. Despite these varied experiences, the disappointing results remain consistent, even as we fast-forward to today, in 2024. I’ve come to believe that the invisible disability of mental health—combined with a lack of staff training and experience—is at the heart of the problem.

While IEPs and 504 Plans are designed to provide accommodations for students with disabilities, their success hinges on effective implementation. Even with the best plans, including Manifestation Determination Review (MDR) meetings aimed at addressing and improving these plans, the lack of follow-through can render them ineffective. I’ve witnessed some exceptionally talented staff members over the years, but they are few and far between, often lacking the support they need from their teams to make a lasting impact.

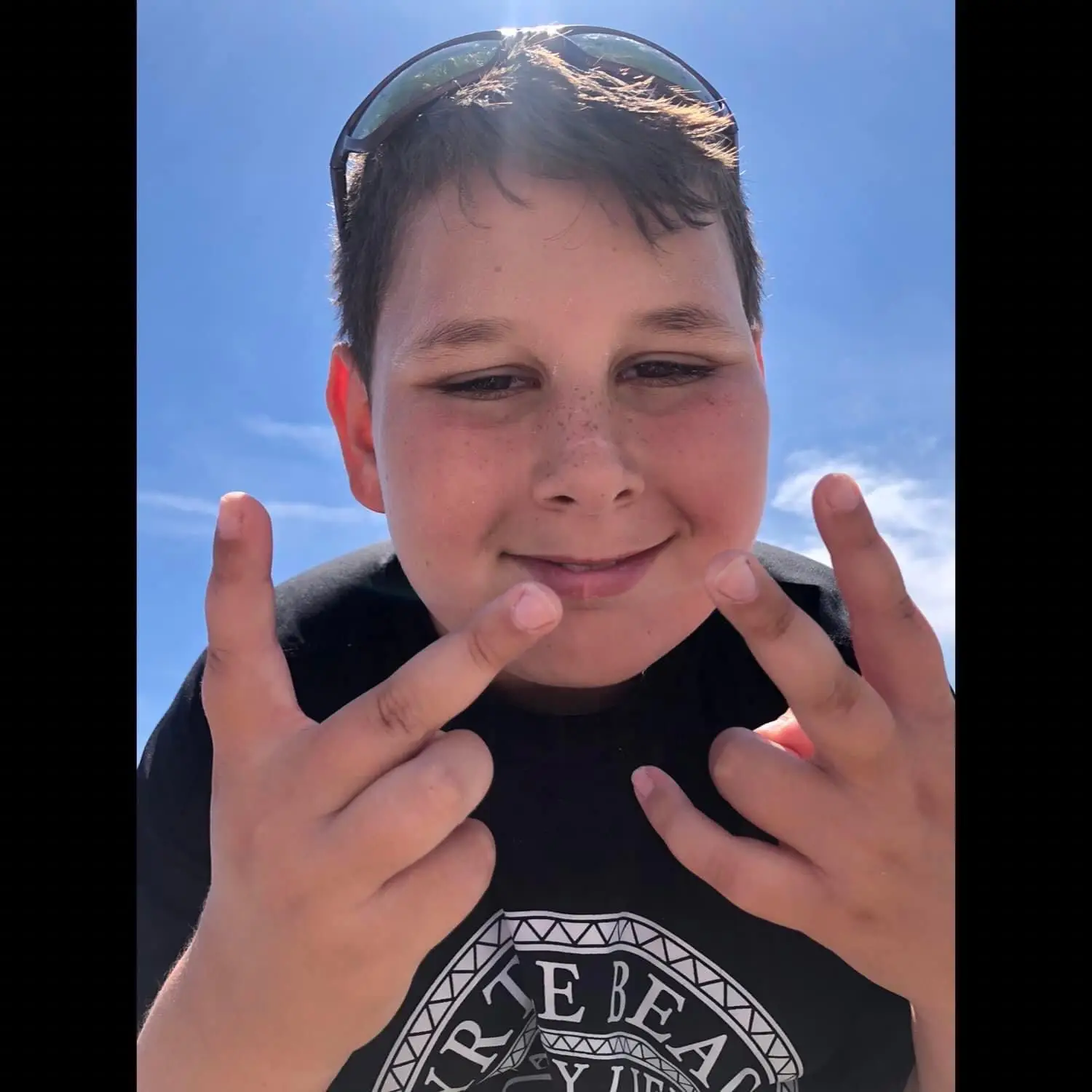

All too often, attention shifts to students with mental health disabilities only after a situation escalates. An incident report is written, detailing every misstep of the child in that moment. These reports rarely acknowledge what the staff could have done differently. This oversight is particularly frustrating because these children often work the hardest to have a good day. My son, like many other kids, has never missed a day of school by choice. He attends counseling weekly, works with a psychiatrist to adjust medications—medications that sometimes produce indescribable side effects—and continually fights for his success.

Yet, the system frequently penalizes these students and their families. For instance, school administrators may hold parents accountable for their child’s medical-related absences, such as 10 unexcused absences, even when these absences are tied to necessary counseling appointments that can’t be scheduled outside of school hours. Parents then find themselves in court, forced to watch irrelevant videos depicting gang life, which seem to be a misguided attempt to teach parenting skills indirectly, instead of offering direct, meaningful support to families in need.

After 25 years of witnessing these systemic failures, I am inspired to advocate for change. It’s time to acknowledge that our current approach is not working. School administrators can’t simply sit back and congratulate themselves on a broken system. Instead, we need to bring experienced, brilliant, and open-minded innovators to the table to create something better for our youth with mental health challenges.

Our children deserve a system that recognizes their efforts and supports their success, not one that focuses solely on their shortcomings. Let’s shift the focus from merely managing crises to fostering environments where students with mental health disabilities can thrive, and their families can feel supported rather than judged.