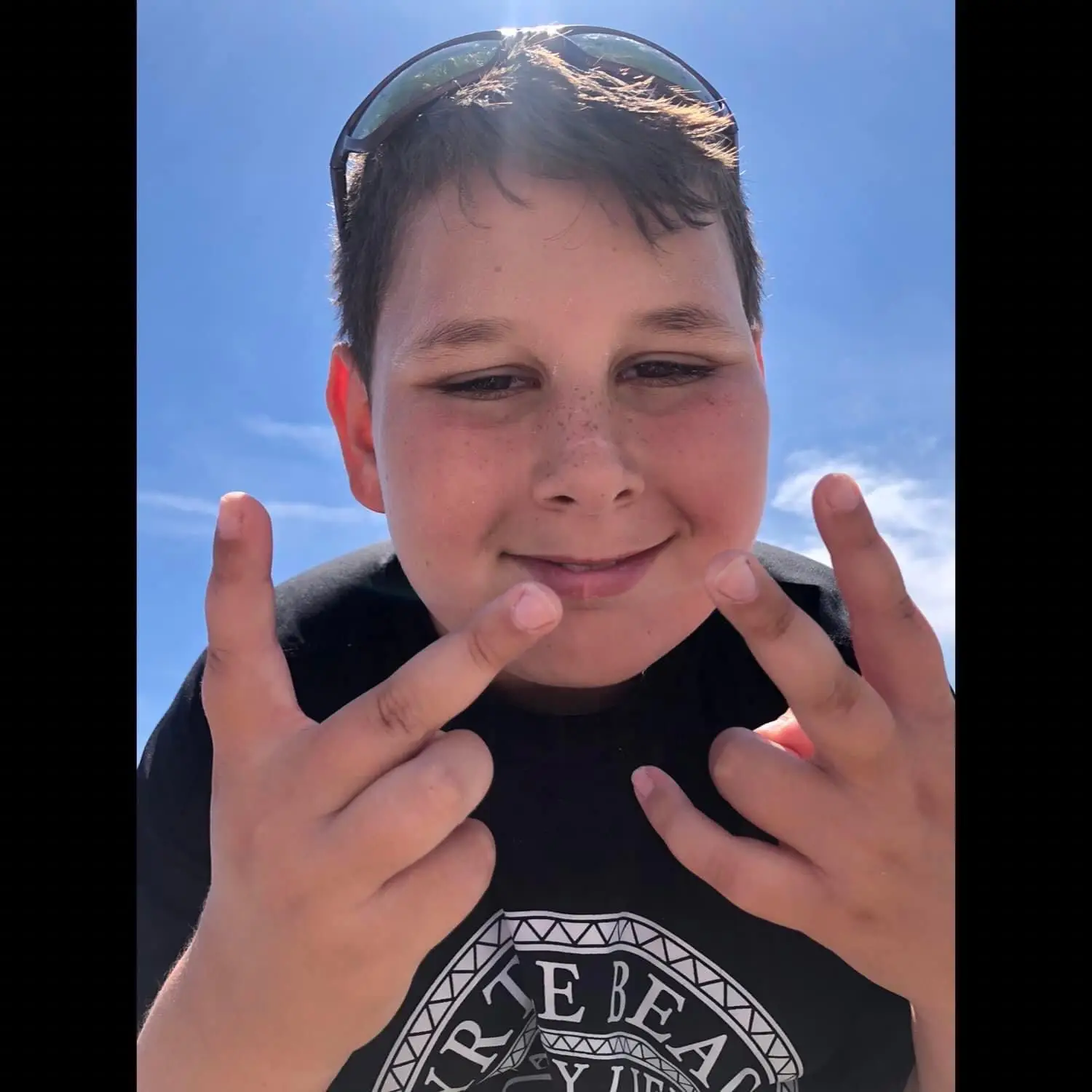

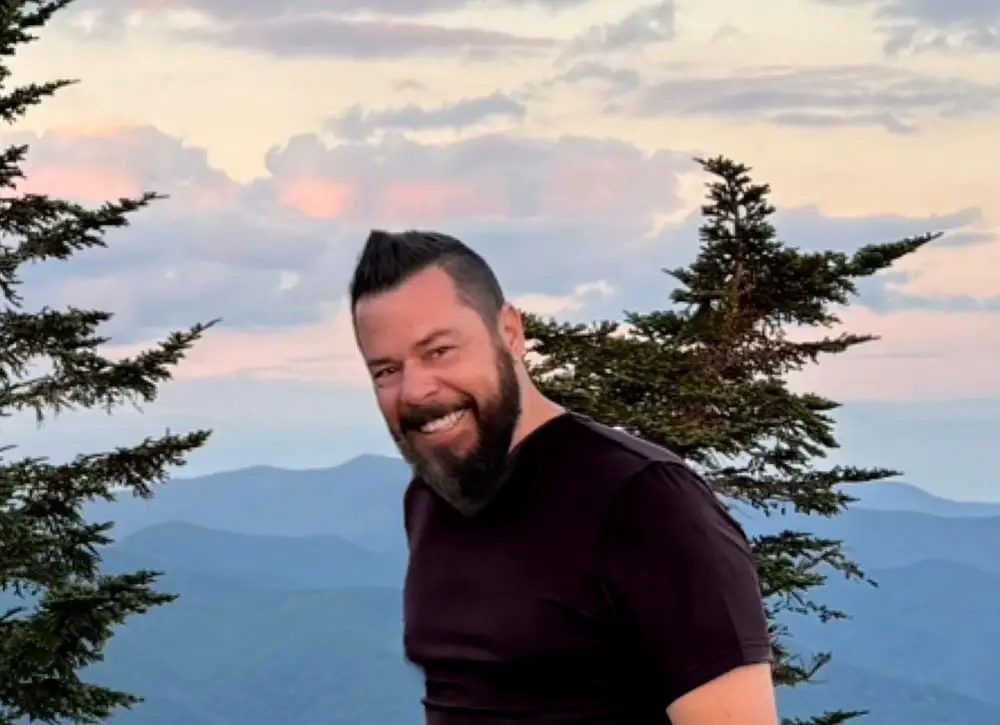

As you all know, our son Grayson has been diagnosed with Bipolar Disorder, and we’ve had to fight every step of the way to have our voices heard. For a long time, our concerns weren’t taken seriously because Grayson didn’t exhibit these behaviors at school. But at home, it was a very different story—our family lived through hell, enduring his bouts of rage and anger. He sometimes lashed out physically at anyone in his path. Grayson often called the police on us when he was in crisis until one day an officer explained to Grayson the importance of using the service correctly.

Through counseling, medication, and setting firm boundaries, we’ve been able to curb these behaviors at home. While it’s not perfect, Grayson is in control about 85% of the time, which is a huge improvement.

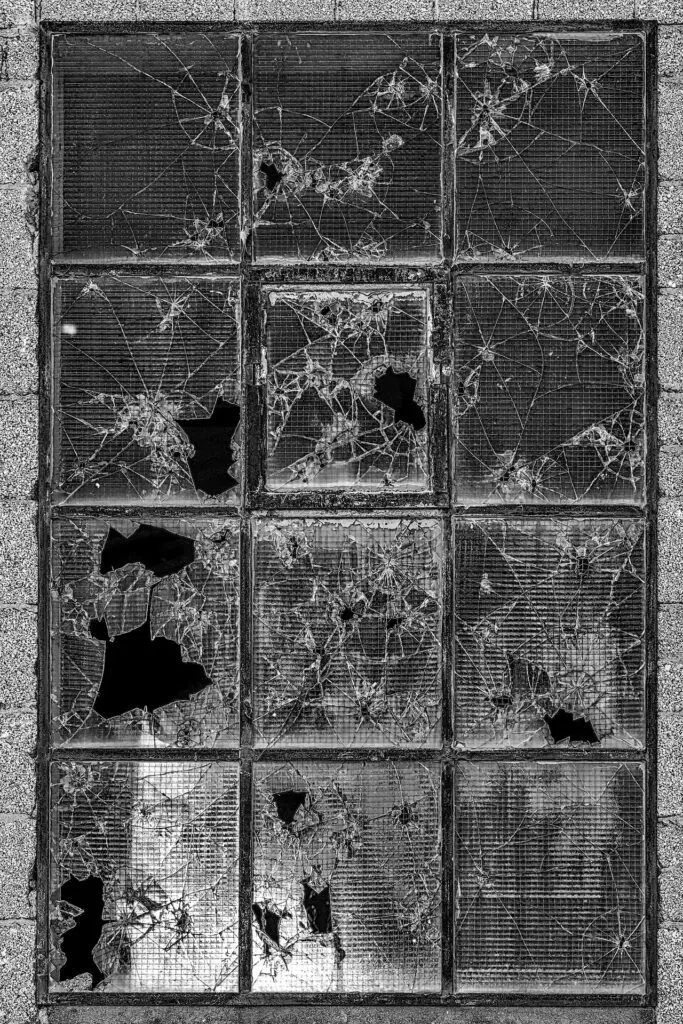

Fast forward a year, and these same behaviors have started showing up at school, leading to a cycle of out-of-school suspensions, waiting for MDR (Manifestation Determination Review) meetings to determine if the behaviors are linked to his disability, returning to school for a few days, and then landing in crisis mode again.

When we first started this journey, the school system approached the situation with behavior plans and goals, treating Grayson like he was simply a “bad kid.” After countless meetings and suspensions, we finally secured an IEP (Individualized Education Plan) for him. In theory, this was supposed to unlock access to additional services and rights for Grayson. But in practice? We’re still stuck on the same rollercoaster.

The school advertises RBHS (Rehabilitative Behavioral Health Services) counseling for children with behavioral or mental health challenges. To say this has been a disappointment is an understatement. None of the RBHS counselors we’ve encountered have been able to de-escalate Grayson during a crisis—in fact, some have even escalated him further.

Grayson has eloped from the school building three times, and last week, he ran off school property to a main road. Six staff members, including a security guard, stood about 20 feet away and let him sit on the curb of that busy road while they waited for the police or his father to arrive and de-escalate him. I am at a loss as to what the school’s safety plans are for situations like this. Why wasn’t a CPI (Crisis Prevention Intervention) hold initiated before he made it off school grounds?

It makes me wonder: If a child in a wheelchair was rolling toward the road, would they have acted faster? Of course, they would have. That child’s disability would have been visibly obvious. But Grayson’s disability isn’t something you can see, and because of that, it often feels like his safety—and his dignity—are treated as less important.

This incident is just one example of the challenges we’ve faced. The stigma surrounding mental illness persists, and it won’t change unless we demand change.

We will have no choice but to hold people accountable—just as our son is held accountable for his actions. Have you been through a similar situation? Let’s work together to advocate for children like Grayson and bring meaningful change to how mental health is addressed in our school systems.